On: “Biological causal links on physiological and evolutionary time scales”

In a recent feature article published in eLife, Karmon and Pilpel discussed the “bi-directional causality” of biological systems and the need to recognize physiological and evolutionary types of causation. While I certainly agree with the general premise that both types of causality should be considered, and I appreciate their apparent wish to draw attention to evolutionary biology, there are a number of problems with their article that I would like to briefly discuss here. These can be put generally into three categories: 1.) Under-appreciation of evolutionary biology as a field; 2.) Under-appreciation of the long literature on this subject; and 3.) A lack of seriousness about the philosophical difficulties of what they claim to uncover.

1.) The main takeaway of their article is that “the reasoning of many biologists [is] seemingly more prone to focus at first on the effect acting on the short-term, physiological time scale explanation and not on the processes that take millions of years to manifest themselves” and that “our reasoning is influenced by certain biases that might prevent us, in some cases, from seeing the full picture.” Ironically, they seem unaware that there are many scientists who work on both physiology and evolution. Molecular evolution is a vast field with several dedicated journals, and much of it is dedicated precisely to understanding the way these two types of causality work together. In fact, if you did a cursory search for recent reviews on molecular evolution, you’d be hard pressed to find one that didn’t at least touch on this subject, if only tacitly (here and here are two in my sub-field of nervous system evolution). Karmon and Pilpel’s paper may be interpreted as trying to attract other types of biologists to evolutionary biology, but why not just do this explicitly?

Another, more revealing part of their paper states that “under certain conditions a bi-directional [causal] effect, both physiological and evolutionary might be at work.” This is an important misunderstanding of evolutionary biology. There is always an evolutionary effect because everything in biology, at least every composite thing, has evolved. A phenotype, whether it be a molecular system or the wing color of a bird, doesn’t have to have been selected for to have been caused by evolution (see this famous paper on the subject).

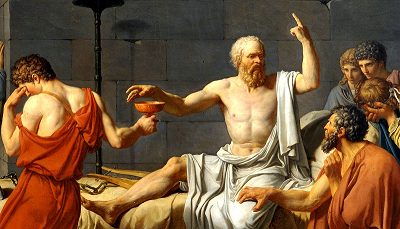

2.) The authors seem unaware that their idea has been thoroughly discussed by biologists for over 2,000 years. They state (after the suggestion of a reviewer) that the “proximate/ultimate causation” distinction was “introduced” by Ernst Mayr in 1961. While it may be true that Mayr helped coin these terms, the idea was clearly already in circulation, and had been referred to by Julian Huxley, William James, and many others in a variety of fields (see Dewsbury 1999 for a nice summary). More thorough discussions of what the authors call “bi-directional causality” were made by the titans of the modern synthesis, including Dobzhansky and Simpson. And it seems amiss not to even mention the name of Tinbergen. For a recent, thoughtful, example, see this review by Harms and Thornton. But these thoughtful writers are only the recent tip of a long, even perennial, discussion stretching back millennia. The distinction the authors draw between physiological and evolutionary causes was already being discussed by the Socratic school of philosophers in ancient Athens, and was most famously stated in Aristotle’s account of the four causes in the Physics:

Aristotle’s Four Causes, which I’ve grouped very tentatively under two headings to show the connection to Tinbergen

- Materialistic

- Material cause: the material of a thing

- Formal cause: the look of a thing

- Non-Materialistic

- Efficient cause: a things first mover

-

Final cause: the telos or end of a thing

Tinbergen’s Four Questions

- Proximate

- Mechanism

- Phylogeny

- Ultimate

- Ontogeny

- Adaptation

Aristotle was a complex and subtle writer, and this is not the place to unpack similarities and differences between his and modern conceptions of cause (I recommend Sachs, Bolotin, and Coughlin on the subject, and Heidegger for the bold), but suffice it say that “bi-directional” causality is not a new idea.

3.) This leads us to the last subject: whether the authors have appreciated the philosophical implications of “bi-directional causality.” I will start with their claim that “proximate cause addresses the question of “how?” and the ultimate cause addresses the “why?” This is a strange statement. (In the authors defense, they are not the first to make it.) But surely we could just as easily say that evolutionary biology teaches us how a biological object came to be, and that physiology teaches us why “short time-scale” phenomena happen. This may seem like silly quibbling (though I would argue that semantics are pretty important in biology, as does Koonin), but it actually exposes the complexity of the problem. Ultimate and proximate explanations both answer the question “why?” They also both answer the question “how?” though, tellingly, that seems less important.

The way we answer the question “why?” is deeply important because it is our touchstone for understanding, and the proximate/ultimate distinction suggests that we do this in at least two ways in biology. Is it possible that we have multiple, contradictory ways of answering this crucial question? Aristotle thought so, or that at least is my reading of the opening line of the Physics, where he gives not one but three ways we answer the question, each separated by the Greek ἢ, “or.” Interestingly, only one of these is causality. The other two are “elements,” what we would now call fundamental particles, and “sources” or “principles”, which we might now call forces. All three of these are examined throughout the book and, I think, found wanting. The famous statement of the four causes in Book II is just one of these examinations.

A fuller exposition of this topic is far beyond my scope here. Suffice it to say that there are profound philosophical questions raised by the way we explain biological phenomena, and that these go back at least to that most original biologist, Aristotle. It is also worth noting that the old trope “correlation does not imply causation,” which the authors employ, is being reexamined in the context of Bayesian statistics (Pearl).

In sum, while I appreciate the authors’ attention to this problem, I think they do a disservice by not appreciating the complexity of the problem, its deep history, and the attention being paid to it by a huge number of working biologists.